Older women have been recognised as the fastest-growing group of homeless people in Australia in recent years. Yet until now we have not known exactly how many older women are at risk of homelessness. Our research, released today, finds about 240,000 women aged 55 or older and another 165,000 women aged 45-54 are at risk of homelessness.

The startling data from our research give us a much better picture of the scale of the problem. We also quantify the impacts of the various factors that may increase women’s risk of becoming homeless.

Effective policy is grounded in quantifying the nature and complexity of issues. To date, a limited but growing number of studies have highlighted the experiences of older women who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. But few studies quantified the numbers at risk and the factors that increase the risk.

What puts women at risk?

Older people are generally considered to be at less risk of homelessness because of their higher rates of home ownership. But increasingly unaffordable housing has added to concerns about the circumstances and living situations of older people who do not own homes, have limited wealth and savings and do not have the benefit of living in social housing. These households rely on the private rental market and are at considerable risk of housing affordability stress and hence homelessness.

To examine risk profiles, we constructed an empirical model of risk of homelessness since the 2007-09 Global Financial Crisis using data from the Household, Income and Labour Dynamics in Australia (HILDA) Survey. The modelling included people who hold a mortgage or pay rent in private or public housing and are aged 45 or older.

This work found older women are more likely to be at risk of homelessness if they have one or more of the following characteristics:

- have been at risk before

- are not employed full-time

- are an immigrant from a non-English-speaking country

- are in private rental housing

- would have difficulty raising emergency funds

- are Indigenous

- are a lone-person household

- are a lone parent (but little evidence for those never married).

We estimated these profiles using a statistical model to analyse the relationship between homelessness risk and the characteristics of interest. We controlled for other characteristics that are likely to influence the risk of becoming homeless but which were not the focus of the study.

Risk factors compound each other

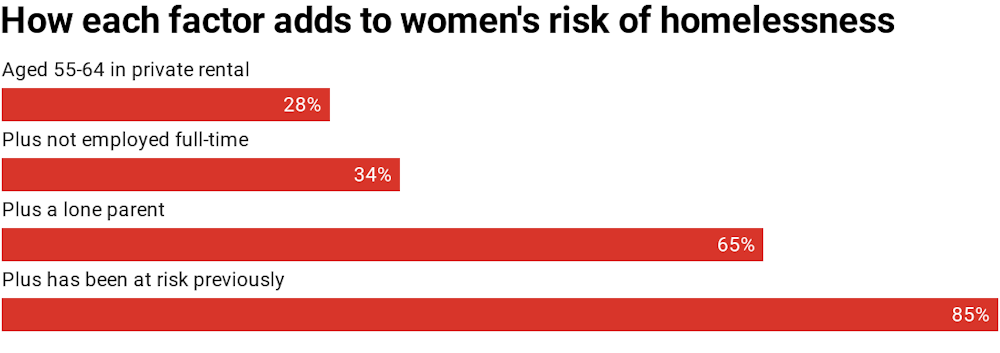

Multiple factors compound the risk of being homeless. While noting sampling limitations (small samples in subgroups of the data and annual volatility), the HILDA data for the post-GFC period suggest:

- for women aged 55-64 in a private rental, about 28% are likely to be at risk

- for women who are also not employed full-time the percentage at risk increases to about 34%

- for those who are also a lone parent the risk rises to over 65%

- the risk increases to over 85% if, in addition, they have experienced at least one prior occurrence of being at risk.

Clearly, a person’s propensity to be at risk of homelessness is cumulative over time.

Why the numbers at risk will grow

Our estimates of the numbers of people at risk are accurate to within plus or minus 10%. Based on Australian Bureau of Statistics population projections, it is clear that, without changes to policy, these numbers are likely to increase due to one important factor. The model shows a lone-person household is a dominant factor in increasing the likely risk of homelessness.

Lone-person households are expected to comprise 24-27% of all households by 2041. This equates to between 3.0 and 3.5 million Australians (of all ages). Female lone-person households are projected to increase by between 27.6% and 58.8% (ABS 2019b).

Australia has made little policy progress on housing affordability. We also have a severe shortage of social housing to meet demand. This points to the need to pursue other avenues to improve the lives of older low-income households.

The Ageing on the Edge Older Persons Homelessness Prevention Project – funded by the JO and JR Wicking Trust and administered by Housing for the Aged Action Group (HAAG) – has worked over the past five years to give voice to these older women who are homeless or at risk of homelessness. The project works with interested agencies (government and non-government) to identify and promote early intervention and prevention strategies and to lobby for government policy change.

Of course, there is one simple answer to achieving long-term outcomes that allow people the basics of a decent older age: an appropriate affordable home.

Source: The Conversation

Authors: Debbie Faulkner (Senior Research Fellow, UniSA Business, University of South Australia) and Laurence Lester (Senior Research Fellow, Centre for Housing, Urban and Regional Planning, University of Adelaide)